The Primary Case for Political Change: Why the Long-Term Benefit Outweighs Short-Term Risks

Wesam Charkawi

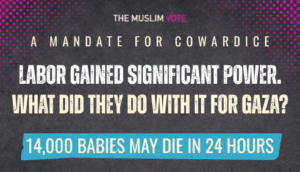

The Muslim Vote acknowledges concerns from those who conflate Donald Trump’s rhetoric with fears of abandoning Labor and inadvertently aiding Liberal leader Peter Dutton. However, this comparison is misleading and fails to account for the fundamental difference in political agency. In Australia, The Muslim Vote has no objective or aim to help install Peter Dutton in power, nor does it seek to embolden policies that are detrimental to the community. The aim is not to shift support from one oppressor to another but to build genuine alternatives that break the cycle of political dependency. The existence of independent candidates in key seats is not a reckless gamble but a calculated strategy to force mainstream parties to engage with the community on equal terms. The real political failure would be to remain locked in a framework where fear dictates every decision, ensuring that the Muslim vote remains a tool for others rather than a force for itself.

The Core Question: Will the Community Be Better Off?

The fundamental issue at hand is not whether certain risks exist—because risks always exist—but whether the community will be better off in the long run by seeking change. The status quo has not delivered meaningful progress, and the reality is that incremental engagement within the current system has yielded minimal results. If the answer to this question is yes, then all other considerations become secondary. Political change is not a luxury; it is necessary for a community that wants agency over its future.

The Fallacy of Fear-Based Politics

Those who argue against challenging the current power structures often invoke fear as their primary deterrent: What if Peter Dutton wins? What if the Labor Party retaliates by ignoring the Muslim community? These are speculative threats that, while plausible, serve to entrench stagnation rather than inspire progress. Fear-based politics assumes that maintaining a flawed status quo is preferable to taking the risk of transformation. But history shows that communities who refuse to challenge the status quo end up politically irrelevant—taken for granted at best, actively sidelined at worst.

The Illusion of Guaranteed Support and the Alternative Path

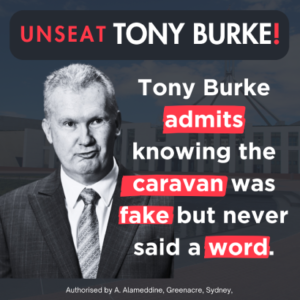

The concern that Labor may shun the Muslim community if it organises for political change is based on the false premise that Labor’s support is currently dependable. The reality is that Labor has already demonstrated that it is willing to overlook, marginalise, and outright dismiss the community when politically convenient. However, the Muslim Vote has put forward an alternative: a viable independent candidate in key seats where the Muslim vote has the power to decide the outcome. This is not an empty protest—it is a strategic realignment. Instead of begging for recognition, the community is now in a position to actively shift the balance of power by putting forward representatives who are directly accountable to it.

The Consequence of Inaction vs. the Power of Independents

The alternative to action is not political safety—it is political irrelevance. If the Muslim community continues to operate within the constraints imposed by mainstream parties, it will remain a convenient voting bloc with no real bargaining power. But for the first time, The Muslim Vote is offering an alternative: the ability to challenge and potentially unseat career politicians who have taken the community for granted. By strategically supporting independents in key seats, the community is sending a clear message: its vote is not automatic, and its support must be earned. If that means making safe Labor seats marginal, then so be it. If that means unseating incumbents, that is the natural consequence of ignoring a politically conscious and mobilised community.

The Objective is Political Leverage, Not Political Chaos

The pursuit of political independence is not an exercise in recklessness or ideological purity. It is a calculated and necessary shift toward a more empowered and self-determined political future. The aim is not to inadvertently install leaders who may be more overtly hostile toward the community but rather to ensure that no party—whether Labor or Liberal—can take Muslim voters for granted without consequence. Political movements throughout history have faced similar dilemmas: whether to remain tied to a system that disregards them or to chart a new course with the understanding that power is never given—it is taken. The Muslim community’s political agency cannot be dictated by hypotheticals about worst-case scenarios while ignoring the ongoing reality of an unchallenged status quo that has already demonstrated its indifference.

It is also essential to recognise that political shifts are not linear, nor are their effects immediately apparent. Short-term disruptions are an unavoidable reality of long-term change. If that change means the temporary unintended consequence of other political actors, then so be it—because what matters is that the community is no longer a passive player in its own future. Fear of unintended consequences must not become a justification for self-imposed political irrelevance.

The Long-Term Imperative: A Strong, Independent Political Identity

The most critical measure of success is not what happens in one election cycle but whether the Muslim community emerges stronger, more organised, and more politically conscious in the long term. The goal is not just to influence the next election but to permanently reshape how the Muslim vote is valued. This requires a strategic shift from dependency on any one party to a position where political actors must compete for the community’s support. By building an independent political base in key electorates, the Muslim community ensures that it will never again be taken for granted—because it will always have an alternative to fall back on. If that means suffering short-term setbacks, then so be it—because the alternative is perpetual submission to a system that only acknowledges the community when politically convenient.

Addressing the U.S. Comparison: Fear as a Tool to Control the Muslim Vote

A common argument used to justify continued support for the Labor Party is what happened in the United States. Some Muslims there took a firm stance against Joe Biden due to his complicity in genocide, believing that nothing could be worse. But with Trump’s return, many are now fearful that his rhetoric, which calls for ethnic cleansing and forced removal, proves that the strategy was a mistake. But this argument fundamentally misunderstands the nature of political agency. The Muslim community in the U.S. did not elect Trump; it simply refused to reward Biden for his complicity in genocide. The blame for Trump’s policies falls squarely on those who upheld a broken system, not on those who refused to be political hostages.

The same principle applies in Australia. The question is not whether Peter Dutton will be worse—it is whether the Muslim community will ever have political power if it continues to be manipulated by fear. If Labor knows the community will always vote for it out of fear of the alternative, then there is no incentive for it to change. There is no price for its betrayal. There is no consequence for its indifference.

Fear is a powerful political tool—but it is a tool of control. The moment a community operates based on fear rather than principle, it has already lost.

Conclusion

Why This Argument Trumps All Risks

At its core, the choice is between fear and empowerment. Those who prioritise risk avoidance over meaningful change are, in effect, endorsing a broken system. However, the Muslim community does not have the luxury of complacency. The risks of political engagement are real, but the risk of continued subjugation is greater. The Muslim Vote has introduced a game-changing factor—an independent alternative that directly challenges the entrenched power structures. This means the community is not just resisting the status quo but actively shaping a new one. The defining question remains: Will the community be better off in the long run if it takes control of its own political destiny? If the answer is yes, then every other risk—whether real or perceived—becomes secondary.