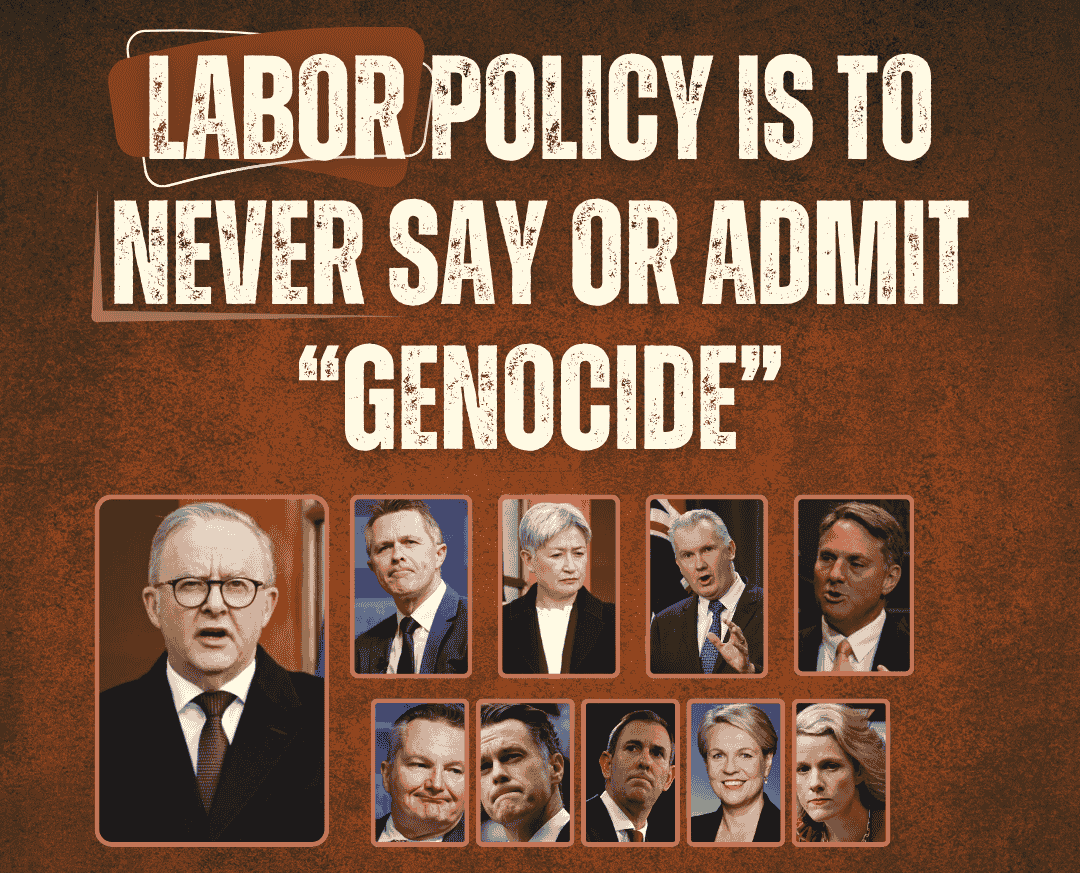

Why Labor Won’t Say the Word Genocide

It’s not a coincidence that you’ve never heard Labor use the word Genocide. Not openly, not publicly, and not formally.

Using the word genocide would carry three immediate consequences, and Canberra knows it.

First, the term would legally bind Australia to act in accordance with the 1948 Genocide Convention and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Recognition would trigger the duty to prevent genocide by all means within Australia’s power, including halting arms transfers, suspending military cooperation, and pressing for international accountability. The moment a serious risk is present, the obligation arises, and that risk has been confirmed.

Second, using the word would require Australia to investigate itself. Domestic law criminalises genocide and complicity. Division 268 of the Criminal Code gives Australian authorities jurisdiction to investigate the role of individuals or corporations. The Defence Department and local contractors are part of the F-35 supply chain now used in Gaza. Amnesty International and the Australian Centre for International Justice have documented Australia’s continued involvement even after the ICJ’s provisional measures against Israel.

Third, it would shatter the political firewall protecting the Government. Admitting genocide would expose the influence of the Israeli lobby and the defence industry on federal policy. It would demand transparency about the A$20 million weapons deal signed with Israel’s largest arms manufacturer after the UN findings — a move critics describe as a “national disgrace.”

First, the term would legally bind Australia to act in accordance with the 1948 Genocide Convention and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Recognition would trigger the duty to prevent genocide by all means within Australia’s power, including halting arms transfers, suspending military cooperation, and pressing for international accountability. The moment a serious risk is present, the obligation arises, and that risk has been confirmed.

Second, using the word would require Australia to investigate itself. Domestic law criminalises genocide and complicity. Division 268 of the Criminal Code gives Australian authorities jurisdiction to investigate the role of individuals or corporations. The Defence Department and local contractors are part of the F-35 supply chain now used in Gaza. Amnesty International and the Australian Centre for International Justice have documented Australia’s continued involvement even after the ICJ’s provisional measures against Israel.

Third, it would shatter the political firewall protecting the Government. Admitting genocide would expose the influence of the Israeli lobby and the defence industry on federal policy. It would demand transparency about the A$20 million weapons deal signed with Israel’s largest arms manufacturer after the UN findings — a move critics describe as a “national disgrace.”

Subscribe to stay informed

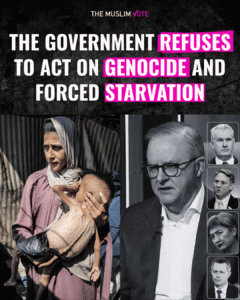

Calculated Avoidance

Knowing the legal obligations that would be triggered, the Government has adopted a language of mitigation, substituting legal application with diplomatic generalities such as “humanitarian catastrophe.” These general and ineffective terms confine Australia’s responsibilities to humanitarian concern while shielding it from the legal and political consequences. The avoidance, therefore, functions as a legal firewall, creating the facade of formal compliance with international norms while structurally shielding it from accountability.

Why this matters?

Once genocide is formally acknowledged, Australia must ask: has it taken “all means reasonably available” to prevent the genocide, under its treaty duty? The ICJ’s jurisprudence makes that obligation real. Australia’s domestic law, particularly Division 268 of the Criminal Code, provides for the investigation and punishment of genocide and related crimes. Acknowledging genocide opens the door to domestic and international liability. Australia’s export controls under the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) require a risk assessment for transfers that might be used in serious violations of humanitarian law. Because genocide is occurring, and because Australia remains materially and diplomatically linked to the offending State, that risk assessment is already triggered and legally unavoidable. As the ICJ held in Bosnia v. Serbia (2007), every State has a duty not only to refrain from genocide but to prevent it using all means reasonably available.

Subscribe to stay informed

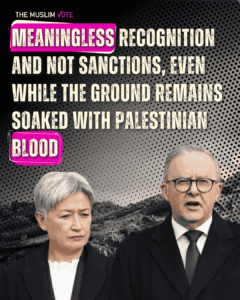

“Staged Recognition of Palestine”

Having made clear that acknowledging genocide would compel Australia to act, the question becomes why Labor would choose to recognise Palestine at all, and what that recognition actually achieves. The answer lies in consistency, not contradiction. Recognition allows the Government to appear responsive to public pressure while maintaining the same structural avoidance that defines its Gaza policy. It recognises Palestine as a diplomatic abstraction precisely to avoid recognising genocide as a legal reality. The pattern is clear: symbolic gestures replace enforceable obligations. By refusing to use the word genocide and instead invoking “recognition,” Canberra confines itself to the language of diplomacy rather than the duties of law. What looks like movement is, in fact, containment, a political instrument to manage outrage without changing policy. The reality is that recognition of Palestine costs nothing for the government, relieves no one, and changes nothing on the ground.